How Infamous Gangsters Bonnie and Clyde Helped Invent Celebrity Culture

Mention “Bonnie and Clyde,” and, for many people, the first thing that springs to mind is the Arthur Penn movie, in which Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway play an impossibly glamourous couple who rob banks, party hard, and die young. Just in case you’ve never seen it, here’s the trailer (and then watch the whole thing; it’s pretty great, and shocking for its time):

The movie is riddled with historical inaccuracies, to put it mildly. The real-life Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were very different, products of the Great Depression and the West Dallas slums who screwed up most of the bank robberies they tried to pull, and managed to survive as long as they did only because of the habitual ineptitude of local law enforcement. They were, in short, a pair of kids (Bonnie was 23 when she died; Clyde, 25) who very quickly bit off more than they could chew.

But a funny thing happened to Bonnie and Clyde on the way to death and obscurity: they found a camera.

Bonnie and Clyde met in 1930 and fell in love immediately; shortly after, Clyde was arrested for robbery and other shenanigans and sentenced to the horrific Eastham Prison Farm, where he cut off two toes to avoid hard labor and killed a bullying prisoner with a lead pipe. When he was released in 1932, he and Bonnie (along with a shifting crew of associates, including some Barrow family members) began a campaign of robberies throughout Texas and the surrounding states.

Instead of pulling off big scores like Dillinger and other famous outlaws of the time, they mostly robbed gas stations and grocery stores, where the tills generally yielded only enough cash to tide them over for a few days until the next stickup. Occasionally they tried robbing banks, although the results were often unsatisfactory and resulted in the local townsfolk firing barrages of bullets as Clyde frantically tried to drive his little gang out of town.

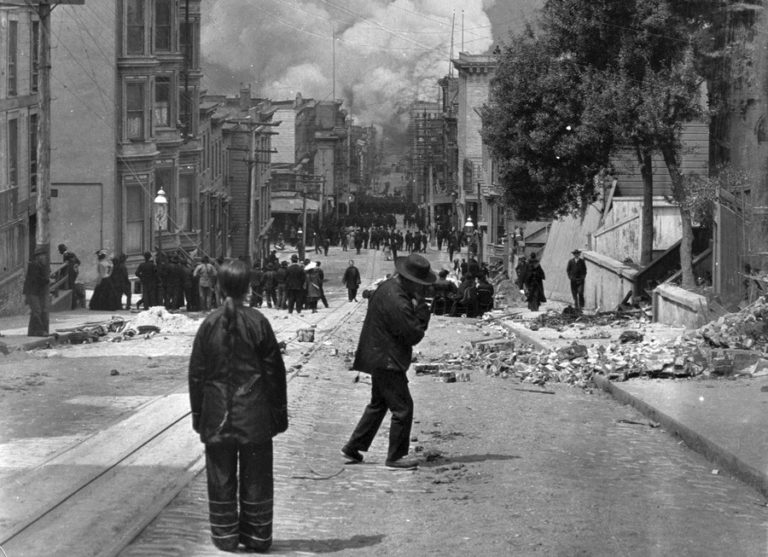

As the months passed, Bonnie and Clyde filled their succession of stolen cars with all sorts of luggage, including a guitar, a saxophone, clothing, true-crime magazines (which sometimes featured wildly inaccurate stories about the couple), and a camera. When they took photographs of themselves, they hammed it up: in one iconic image, Bonnie is standing in front of a stolen V-8 Ford, one foot on the fender, a pistol in one hand and a cigar clenched between her teeth. In other images, they dressed in suits and posed with an ever-increasing arsenal of weapons, including guns taken from police officers.

After a shootout in Joplin, Missouri, the authorities recovered Bonnie’s camera and released the photographs, which turned the pair into celebrities of a sort.

“Few real-life villains had the same roguish charisma that Jimmy Cagney and Edward G. Robinson brought to movie screens,” recounts Jeff Guinn in “Go Down Together,” his excellent biography of the two. But the photos of Bonnie and Clyde “introduced new criminal superstars with the most titillating trademark of all — illicit sex.” Journalists and true-crime hacks leapt at the chance to write “far-fetched stories about these young criminal lovers.”

But as most modern audiences know, there’s always a gap between image and reality. People assumed that Bonnie was a cigar-chomping desperado capable of gunning down lawmen, when in reality she was very much along for the ride — in love with Clyde to the bitter end, even after an auto accident virtually crippled her. The photographs, in conjunction with the lurid fictions spun by journalists, made them seem successful, invulnerable, even rich — when in reality they were skittering between backwoods campsites, sleeping in stolen cars and living rough.

Such was the power of that photograph-generated reputation that, when they were finally gunned down together in May 1934 in Bienville Parish, Louisiana, thousands of people rushed to witness their mangled bodies. Folks were surprised at how small the pair were in real life.

Bonnie and Clyde didn’t birth selfie culture, and they only two of the “celebrity outlaws” who helped define so-called Public Enemy era. But their use of imagery, and the inflamed public response to it, foreshadows some aspects of 21st century celebrity culture. So often, we think our era created something; but in many cases, we’re just repeating, with some variations, what came before.