The animals could feel it coming.

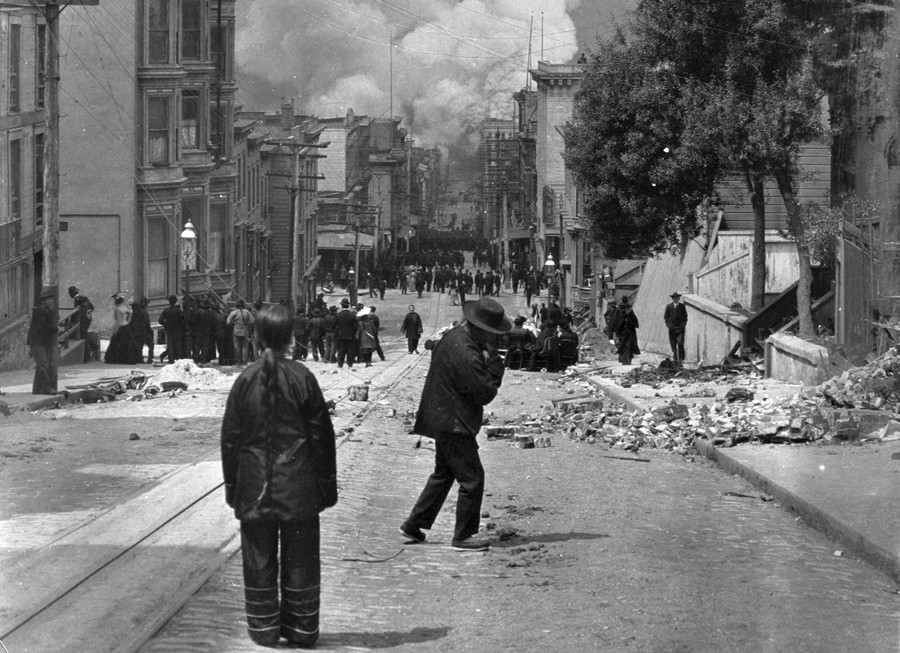

The early hours of April 18, 1906 reportedly filled with the frightened barking of dogs and horses’ panicked neighs. But people have duller senses, and San Francisco, with its half-million residents, slept on until the huge earthquake hit at 5:13 that morning. Buildings crashed down and fire rose up, and for three days all was chaos. By April 21, over 28,000 structures were destroyed, 521 blocks burned, and an estimated 498 lives lost. It was, to many people, one of “the great catastrophes of the world’s history.”

Destruction, though, can often fold into resurrection. Even as survivors cleared the rubble and took accounting of their losses, San Francisco’s political and economic leaders convened with ideas for the city’s rebirth. Their plans centered on turning the now-burned downtown area north of Union Square into a handsome, Daniel Burnham-designed commerical center; to do so, the fire-leveled Chinatown, viewed by those at the top of the local power structure as a hive of sin and corruption, would have to be moved from the city’s heart to its outer environs.

However, the residents of Chinatown had no intention of being displaced. In the face of enormous pressure, and using their financial and political importance to the city as leverage, a loose coalition of Chinese merchants negotiated to keep Chinatown at the same location. For these residents, the fight for cultural survival continued for days and weeks after the earthquake had passed, and the Chinatown that arose from the ashes was a brighter, safer, more prosperous version.

Chinatown had always been a prominent feature of San Francisco, yet the city’s non-Chinese residents saw its culture and customs as alien, even dangerous. After arriving in America, the Chinese as a body resisted assimilation, keeping their language and dress (much to the curiosity and superstitious fear of their non-Chinese neighbors). They sailed to California to search for gold, escape from homeland travesties, and build the Central Pacific railroad; large numbers of them settled in San Francisco, their original point of debarkation and by far the largest city in the state at the time.

By 1859, Chinese immigrants occupied thirty tents lining Clay Street, and by 1906, their presence had extended to a twelve-block neighborhood bound by Kearny and Stockton Streets to the east and west, and Broadway and California Streets to the north and south.

While it is impossible to accurately estimate Chinatown’s population during this expansion (one report at the time said 30,000 souls; later estimates range from 25,000 to 40,000), the effects of overcrowding were obvious. A Special Report by the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco in 1885 found Chinatown “conspicuous and beyond [other American slums] in the extreme degree of all these horrible attributes, the rankest outgrowth of human degradation to be found on this continent.” It was a neighborhood packed with gambling houses, bordellos, opium dens, and temples. Despite all that economic activity, however, only 39 pieces of property within the neighborhood were actually owned by Chinese by 1906; white landlords rented the rest at excessive rates.

Despite these conditions, many Chinese made substantial material progress, establishing businesses and building a supportive community infrastructure. By the time of the earthquake, there were three neighborhood newspapers (the Occidental News, the Chinese World, and Chung Sai Yat Po) and a telephone exchange with eight switchboard operators and two thousand subscribers. In addition to gambling and prostitution, large legitimate business interests operated in the neighborhood: between 1882 and 1906, the number of retail stores in Chinatown grew from 314 to 1,500. These stores acted as conduits to China, importing rice, herbs, opium and other commodities to both San Francisco and the rest of the United States; the duties paid by these Chinese merchants became a major source of revenue for the city. Hundreds of thousands of dollars also came in from tourism.

The reaction of the city and its residents to Chinatown’s growth was one of rising consternation. Racism was a factor in this growing hatred, with Chinese laborers viewed as having “usurped the place of the white laborer”; organizations including the Irish Workingmen’s Party attacked any Chinese who strayed outside their neighborhood. City authorities often justified these attacks, stating in one report that “you cannot, and would not if you could, force American free labor down to the level of Chinese labor.” Such sentiments increased the isolation of Chinatown relative to the rest of the city.

To “clean up” Chinatown, Police raided opium dens and gambling rooms with numbing regularity. City politicians further attempted to dissuade the Chinese residents from remaining in place through legislative action. In 1870, the San Francisco municipality passed a law preventing Chinese labor on public works projects. In 1876, local politicians issued the Laundry Ordinance, which charged Chinese laundries a $60 yearly license, before the courts repealed that law as unjust.

Politicians also restricted the flow of Chinese immigrants into the city. The 1882 Exclusion Act, a national law passed by Congress, allowed only Chinese students, merchants, tourists, and diplomats to enter the country. Even then, these select immigrants were subjected to humiliating interrogations and isolation. In 1903, Mai Zhouyi, wife of a prominent merchant, gave a speech in which she deplored how, upon landing in America, she “spent forty-odd days in [a] wooden house. All day long I faced the walls…like a caged animal. Others — Europeans, Japanese, Koreans — were allowed to disembark almost immediately.”

The Burnham Plan

The Chinese remained despite these actions, infuriating some city authorities, who decried how the “cunning and unscrupulousness of Chinamen enable them to evade our laws” and urged that plans be made to “drive them from our midst.” To this end, architect Daniel Burnham was hired in 1902 to design a more beautiful downtown area, complete with wide streets and parks. Once city authorities approved the Burnham Plan (as it became known), a group of businessmen headed by John Partridge plotted to purchase at least two-thirds of Chinatown, and raze it in favor of those “broad and beautiful boulevards.” They estimated that the real estate in Chinatown, if neighborhood was removed and modern improvements made, would be worth around $25,000,000.

Despite these plans, city officials were unable to move forward: uprooting the entire Chinese population, and their associated infrastructure, would have been prohibitively expensive. The Chinatown situation held in this stalemate until 5:13 on the morning of 18 April 1906.

Rumble

The earthquake lasted for forty-eight seconds. The streets tore open, debris crashing onto the sidewalks. Water burst from split mains, people hurled flailing into the air. City Hall, a monolith of steel and concrete, crumbled instantly, leaving only its framework standing. Jack London, living near the city at the time, arrived to find “the streets humped into ridges and depressions…telephone and telegraph systems were disrupted…all the shrewd contrivances and safeguards of man had been thrown out of gear by [the] twitching of earth-crust.”

Chinatown, as with the rest of the city, found itself reduced to a state of utter dysfunction. Hugh Kwong Liang, one of the relatively few Chinese witnesses whose statements have survived, described awakening to see “pieces of plaster falling down like water… [as I] ran into [Washington] street, the building across from our place collapsed.” Alice Sue Fun, a seven-year-old girl also living on Washington Street, recalled that “everything fell off the shelves. We had one of those stoves made out of brick. My father cooked and the stove had crumbled… we had to evacuate the place.”

The tenements had been poorly constructed and rickety, and now many fell, their residents escaping into the streets. Some fled Chinatown completely. Many ran into temples to pray for salvation and appease the furious Earth Dragon. But as the world collapsed around them and buildings caught fire, many of these supplicants perhaps lost faith in prayer.

When the earthquake hit, a herd of cattle being led to the stockyards at Potrero panicked and stampeded. They charged down Mission Street, goring a saloonkeeper, and police had to open fire on the animals. One steer, escaping into Chinatown, terrorized residents; thinking the beast another bad omen, they hacked away with knives and machetes until an arriving officer shot the animal dead.

Broken gas lines and shattered lamps ignited. The first major fires were reported on Market Street, and soon these spread rapidly to the north and southwest. “Within an hour after the earthquake,” Jack London wrote, “the smoke of San Francisco’s burning was a lurid tower visible a hundred miles away.” As flames consumed shacks and mansions, huge hotels and seedy lodging houses, a huge mass of the city’s population tried to reach the Ferry Building and its boats, or, failing that, the higher ground of Golden Gate Park. Some richer citizens purchased horses or help to carry their goods, but the majority gamely dragged or carried only those possessions they could carry to safety.

With many water mains broken, the fire department had only a limited supply of water. As a last resort, they began using dynamite in an attempt to create firebreaks; according to one source, “during [April 18] a blast could be heard in any section at intervals of only a few minutes, and buildings not destroyed by fire were blown to atoms.” This strategy had some unfortunate results. The west end of Chinatown caught fire when a group of firefighters, having run out of dynamite, resorted to black powder to clear buildings along Kearny Street: the blasts were too weak to vaporize the structures, but strong enough to rocket flaming wood onto structures at Chinatown’s edge, setting fire to them.

Overturned stoves and candles, meanwhile, kindled other parts of the neighborhood. The major streets soon became furnaces, and Chinatown was doomed. Thousands of residents abandoned attempts to retrieve their possessions in the rubble and ran screaming from the firestorm. Some made it down Market Street to the Ferry Building; others made their way to open spaces such as Washington Square.

On April 20, the firefighters managed to stop the Chinatown flames at Van Ness Street, using a motley assembly of tools including wine jugs, scavenged dynamite, and wet blankets. Less than twenty-four hours later, virtually every fire in the city had been extinguished. The whole of San Francisco was reduced to smoke and ashes.

Aftermath

Martial law now ruled the streets. Mayor E.E. Schmitz had issued an illegal proclamation on the night of April 18 that gave officers the ability to shoot looters on sight. Federal troops and National Guard forces released by Governor George Pardee arrived in the city within a day and took up positions, many helping firefighters with the explosives. The army, civil and state authorities worked out an order by which “the northern part of the city should be assigned to the federal troops, the central part to the national guard…[the city] was divided into eight military districts.”

Even though these soldiers had been installed to prevent looting, many could not resist taking advantage of the situation. As early as April 21, the Chinese Consul General of San Francisco, Chung Pao-hsi, complained that the troops were systematically stripping Chinatown in the wake of the flames. General Maus blandly replied that soldiers had orders to drive off any groups of looters, military or otherwise.

When the city began to return to some semblance of normal life, Maus’ claim was further put to the test. On the morning of April 27, over a hundred off-duty National Guardsmen crossed over from Oakland and began looting Chinatown in earnest. These troops, part of the Seventh Infantry Division, Company D, were driven off only when sentries “fired [shots] at neighboring walls, before which the looters fled like so many sheep.”

Company D was only the beginning of an avaricious tide. Soon came looters searching for exotic Chinese wares to sell; came sightseers who wanted souvenirs; came robbers interested in the safes and lockboxes. Yet Chinese residents themselves were still forbidden from entering their own neighborhood. One observer, E. E. Van Loan, observed that “I did not see a single Chinaman in all the complete ruin [of Chinatown]…The Yellow men have fled from the place, and the only human beings I saw were two Italians poking about in the ruins.”

Where had the Chinese fled? As the city had burned, the only thought of the citizenry was escape, with their material possessions if possible. Refugees assembled anywhere far away from the flames, and relief agencies, including the American National Red Cross, immediately scrambled to meet their basic needs.

As the fires were brought under control, a massive amount of relief was delivered to the city. William Randolph Hearst personally contributed a good deal, while trainloads of food and necessities rumbled in from Los Angeles and, later, other cities further east. President Theodore Roosevelt and Congress passed a bill for $500,000 worth of relief. By June 1, countries from Scotland to Cuba would send over $9,116,944.11 to the Red Cross for use in San Francisco.

But the population would need to be moved while the city underwent reconstruction. In relatively short order, the departments of Camps and Warehouses and of Relief and Rehabilitation were formed. Under the watchful eye of several committees’ worth of high-level officials, these departments worked to erect tent cities, supply families with aid, care for the wounded and aged, and employ those newly destitute. Soon breadlines, clean-water pumps, tent cities, temporary homes, and even barber shops were up and running.

Return

Despite all this activity, Chinese residents seemed to disappear from the official logs. The San Francisco Relief Survey, compiling various aspects of the city’s recovery, found that “a population of 10,000 Chinese was represented by only 20 families drawing rations.” Furthermore, the Relief Survey claimed, “[the Chinese] did not ask for much…not over 140 applications for rehabilitation were assigned to Chinese; ten thousand dollars is a liberal estimate for the value of relief given to the [Chinese].”

Instead, in the weeks following the disaster, Chinese residents set up camp in vacant lots and parks away from the other masses of citizenry. Many who knew people in other towns left San Francisco forever. It seems likely that a majority of them did not feel willing to trust the establishment that had treated them so poorly over the past several decades. There may also have been deliberate attempts, not widely discussed in the literature, to dissuade the Chinese residents from attempting to claim a larger section of the relief “pie” in the days following the disaster.

But if they were distrustful or apathetic about relief housing, they were zealous to reclaim their original territory. For the week following the earthquake, city authorities prevented them from doing so, citing the ostensible need for troops to continue protecting the area. Only on April 29, after Consul General Chung Pao-hsi and other Chinese community leaders petitioned Governor Pardee and the Army Generals, was the first contingent of 300 Chinese residents allowed into the guarded area to search through wreckage and take scope of the damage. The fire had left many with nothing, although it seems some of the richer merchants and businessmen had enough out-of-city investments and valuables in untouched safes to stay relatively solvent.

City authorities had no intention of letting Chinatown rebuild. Echoing their sentiment, Syndey Tyler, in a book written soon after the disaster, claimed the removal of Chinatown would greatly improve the nature of the future San Francisco. Likewise, the Oakland Monthly stated that the fire had “reclaimed to civilization and cleanliness the Chinese ghetto.” The mayor had been elected with the support of the very labor forces that had been antagonizing the Chinese community for decades, and he had no intention of disappointing his constituents by allowing things to revert to the way they were. He thought, along with many other prominent political and economic figures, that the Chinese community should be moved far south to Hunter’s Point. Once this occurred, the Burnham Plan could be initiated for downtown.

Hunter’s Point sits on an expanse of mud flats. At the time of the earthquake, it was an area of slaughterhouses. One can only imagine the stench in the air, or the large amounts of animal waste polluting the environment. For the city’s political establishment, the idea of moving Chinatown to Hunter’s Point was so favorable that it arose again and again in discussion, even as other locations were considered and discarded.

The Chinatown community was less than thrilled at the prospect, but for April and May generally remained silent on the issue. Many found themselves too busy trying to repair their lives: newspapers reported that Chinese property owners intended to begin anew where their holdings had been, and that “Chinese leaders had contacted famous lawyers who…said that anyone who owned or leased properties could legally build new buildings.”

For the city’s leaders, however, a sticking point developed that had nothing to do with building ownership. If the Chinese merchants were forced to move, it would disrupt both tax revenues and duties from trade with China. In 1905, Chinese merchants are thought to have paid almost fifteen million dollars in import duties; if they left the city altogether, or even paused their operations, it would have resulted in significant financial losses for San Francisco.

In one of the great ironies of the battle, the white owners of property in Chinatown campaigned heavily for the Chinese return, for the Chinese residents and merchants were willing to pay vastly inflated rents and leases for space. These economics were likely the deciding factor in the city deciding to “back off.” Throughout the summer of 1906, reconstruction began in earnest in the original Chinatown, and the returning residents celebrated victory against the “outsiders.”

In the eyes of city authorities, however, this return was conditional. Herbert E. Law, Chairman of the Subcommittee for Street Planning, declared in May that “it is important to have the streets of Chinatown laid out in a better manner…we ought to do away with the blind alleys and have the thoroughfares so arranged that the locality will be accessible in every part and be easily policed.” If the Burnham Plan could not be implemented in full, then downtown would have to be modified as best as possible to fit the Plan. The city further specified that buildings in the area needed to be made of fire-proof material.

This metamorphosis encouraged Chinatown’s community to revamp, and in some cases to self-police. Merchants grouped together into the Six Companies, which systematically denied gamblers places to play their games, and the Peace Society, which mediated tong disputes and, by 1924, moved to dissolve the gangs themselves.

These measures were far more successful than the city police raids of decades past, which had done little more than stir up rage within the community. This is not to say that Chinatown emerged after the earthquake as a new utopia; but there was much improvement over what had existed before. Within a few years, Chinatown had become more prominent and politically powerful than ever before, buoyed by tourism and a recognition of its collective economic impact.

One of the perpetually fascinating aspects of disasters is how the people survive and recover afterwards. The act of rebuilding, of reassembling life from the pieces left in disaster’s wake, seems symbolic of humankind’s indomitable will and unbreakable spirit.