How Napoleon’s Ego (and the British Navy) Ruined His War on Egypt

The story of Napoleon in Egypt remains noteworthy for several reasons. First, it is a key examine of how, even if its tactical system is superb enough to decisively win battles, an army can still lose a campaign if its grand strategy is fatally flawed. If you want ultimate victory, you must always think with as broad a scope as possible.

Although Napoleon won every battle against Egypt’s ruling Mamelukes, his invasion was built on unsound strategic thinking that left his army vulnerable to having its supply lines cut by the British Navy. Napoleon had immense gifts as a commander, but all the tactical brilliance in the world can’t help you if your supply and logistics are cut off.

Following his victorious 1796 campaign in northern Italy and his expulsion of the British from Toulon, the French Directory named Napoleon commander of the Army of England, whose ostensible purpose would be a cross-channel invasion of Britain. Napoleon, like many commanders before and since (including the Germans in World War II), concluded that such an endeavor was ultimately impossible: “[The plan is] too chancy to risk la Belle France on a roll of the dice,” he declared. This is ironic, because Napoleon was one of those leaders who liked to bet big on decisive battles and orders, but he was probably correct.

Instead of trying to call on London, Napoleon proposed an assault on India, Britain’s colony at the time. Not only that, he planned to do so by marching through Egypt and the Middle East into Asia. This would serve several purposes: Not only would he snatch India from the British grip, but dominating the Eastern Mediterranean would further allow him to damage his rival’s shipping and military capabilities.

If you took elementary-school geography, you can immediately see the problem here — all the British would need to do, with their world-class Navy, was sail around the Cape of Good Hope if they wanted to completely sidestep the French in the Mediterranean. In addition, any attempt to seize Egypt and the Middle East would require France keeping its sea-based supply chains open — a risky proposition, considering that the British dominated Naval combat during this period.

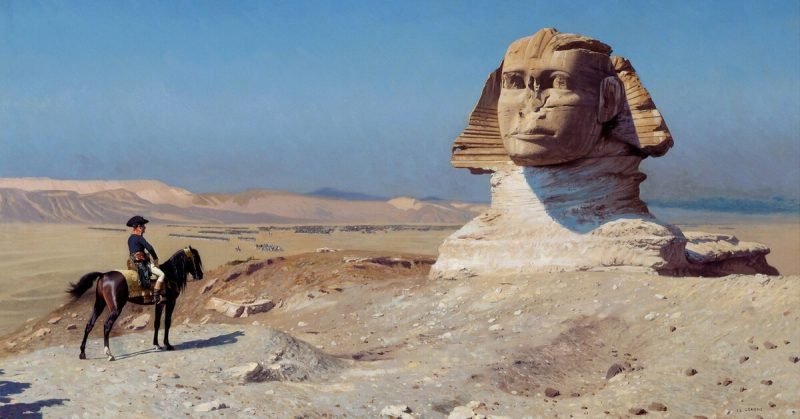

Napoleon, however, seemed undeterred. In his megalomania, he envisioned an Egyptian campaign as the first step in seizing the entirety of Asia. “I saw myself founding a new religion,” he would later declare. “Marching into Asia riding an elephant, a turban on my head, and in my hand the new Koran.”

Whoever told Napoleon as a kid to “dream big” really did a fantastic job. Yet despite his hubris, he failed to think big enough to understand the threat that would fatally undermine his plans.

Egypt at this time was controlled by Murad Ray, warlord and head of the ruling Mameluke families. He was smart enough to realize an existential threat when he saw one. When the French fleet (consisting of 35,000 troops) landed near Alexandria on July 1, 1798, the Mamelukes decided to refrain from attacking immediately. When Napoleon and his army, once unloaded, began their march toward Cairo, the Mameluke cavalry engaged in a raiding strategy, hitting at French stragglers and probing weak points, but denying Napoleon the decisive engagement he craved.

As with so many military campaigns throughout history, the attackers were the least of the French army’s problems — the terrain itself was murder. Much later, Napoleon would write that the desert itself was “most difficult to surmount.” The expedition suffered from a lack of food and water, which weakened and demoralized the troops. This was the first hint of how supply problems would eventually cripple French hopes for conquering and holding the country.

But Napoleon nonetheless advanced; and the Mamelukes, feeling the pressure, decided for direct engagement. Big mistake. Their tactical system was inferior in the face of a well-armed European force. At this point in history, the French liked to arrange their musket-bearing troops into columns that allowed them to pour near-continuous fire into a charging enemy. Moreover, French infantry was drilled and disciplined to a fine polish.

The Battle of the Pyramids

The Battle of the Pyramids (July 21, 1798) illustrated this tactical superiority, especially in the face of cavalry. The day before, alerted to French movements, 4,000 Mameluke cavalry had taken position around the village of Embabeh, right in the path of Napoleon’s advance. Meanwhile, 15,000 Mameluke infantry had entrenched in front of the village, on the east bank of the Nile. On the west side, another 18,000 Mameluke reserve troops waited. Murad Bey was in personal command.

Eager for that decisive battle, Napoleon split his force into two bodies, one on each side of the river (throughout his military career, he was a huge fan of this sort of maneuver). The Rampon and Vial divisions faced the Mameluke cavalry and Emababeh, while the Desaix division marched up the west side of the Nile in order to secure the flank. Each division had formed itself into a hollow square bristling with weapons.

The Mameluke cavalry, fearless, immediately began a frontal charge. The French refrained from firing until the enemy was atop them, then fired waves of bullets, killing hundreds and making the rest flee in disorder. French artillery also fired off grapeshot at point-blank range, adding to the decimation.

Next, the French turned their attention to the Mameluke infantry dug in before the village of Embabeh. The Mameluke infantry broke and fled; trapped between the advancing French and the Nile, they were either slaughtered or drowned trying to escape.

Final casualties: Roughly five thousand Egyptians, versus three hundred French wounded or killed.

The battle demonstrated the strength of the French tactical system, particularly against an opponent ill-suited to handle massed muskets. Napoleon marched unmolested into Cairo on July 24. With Egypt now under French control, Napoleon attempted to calm the population by issuing edicts that portrayed his arrival as predicted by the Koran. This strategy, however predictably, failed. When the population rose up, the French had to suppress them with executions and gunfire.

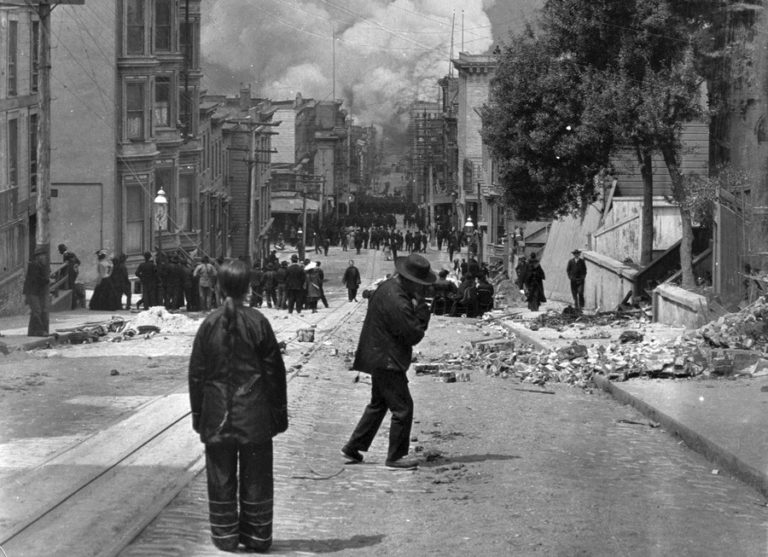

Strangulation

Napoleon knew full well that the British would attempt to attack his campaign via the sea. Accordingly, he anchored his fleet outside Aboukir Bay, near the mouth of the Nile. In a move with massive repercussions later, though, he neglected to adequately plan for the fleet’s supply, much less how the ships could dock and repair.

That made the French fleet a prime target for British Navy Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson, who had 13 ships of the line, one fourth-rate, and one sloop of war (basically, 13 massive warships, one smaller warship, and one relatively tiny (20-gun) vessel). The British, sighting the French fleet in Aboukir Bay on August 1, immediately attacked the French, who were not only undersupplied and ill-prepared, but had lined up their ships in a way that allowed the British fleet to bracket and pulverize them.

This Battle of the Nile resulted in thousands of casualties for the French (some sources have estimated up to 5,000) and the loss or capture of 13 ships. Meanwhile, the British suffered just over 200 killed, with an additional 700 wounded.

Napoleon had failed to take the British Navy (and Nelson’s brilliance) into full account, and now he paid the price for failing to conceptualize broadly enough. With the unimpeded British navy having cut French supply lines and blockading Alexandria, the French army found its situation increasingly dire. This lack of supplies was compounded by the skyrocketing administrative expenses in French-controlled Alexandria. Compounding the issue: Disease and falling morale among the French troops (the plague became an issue). The Mamelukes, having regrouped, began launching raids.

Napoleon’s absurd dream of conquering all of Asia was over before it began. With his communication lines to Europe effectively cut, he fled back to France on August 23, 1799, slipping through the British blockade aboard the frigate Muiron. A worn and demoralized French army surrendered to invading British forces on September 2, 1801, and was gradually repatriated back to France. As Napoleon eventually summed up: “If it had not been for the English I should have been Emperor of the East, but wherever there is water to float a ship, we are sure to find [them] in our way.”

Napoleon blamed his failure on the British Navy (as well he should have), but that’s not the whole story. He didn’t take into account that the citizenry of Egypt wouldn’t greet the French as liberators; he failed to come up with an adequate plan for addressing the inevitable collision with the British Navy; and the power of his dreams obscured his ability to recognize the very real strategic obstacles in his path. His ego, which gave him the confidence to conquer Europe, also fatally undermined his thinking. Let that be a lesson to all of us, even if we have no intention of invading another country.