The speculative-fiction writer Philip K. Dick used amphetamines and other stimulants to transform himself into a 24/7 writing machine. Powered by chemicals, he churned out 28 novels and more than 132 short stories (many of which used drugs as subject matter, including “A Scanner Darkly”). Nor was he alone: If pulp writers didn’t churn out as much copy as possible, they didn’t eat — and if that meant swallowing pills so you could write for two days straight, so be it.

In some ways, the writing business hasn’t changed much in the past century. For thousands of writers, the volume of copy you generate is proportional to how much you earn. Drugs are still a way to power through — I know more than one journalist or blogger who developed a nasty Adderall habit — but often it’s just a combination of caffeine and desperation.

I’m a journalist and editor who also writes pulp fiction on the side, so I’m as aware of the marketplace dynamics as anyone else in the writing business. Over the past year, I’ve been keeping an eye on the evolution of A.I. text generation, which is touted (by businesses) as a way of generating tons of content on the cheap, while derided (by writers) as a potential job killer.

One of the more prominent A.I. text generators has been GPT-2, a “large-scale unsupervised language model” created by OpenAI, a semi-nonprofit (it’s complicated) that wants A.I. and machine-learning tools used in virtuous ways. The relatively new GPT-3 is a further refinement of the underlying technology.

With a training dataset of 8 million web pages (featuring 1.5 billion parameters), GPT-2 was long-touted as capable of achieving “state-of-the-art performance on many language modeling benchmarks.” OpenAI initially refused to unleash it into the wild, fearful that it would be used to generate mountains of “fake news.”

Last year, I tried an experiment where I fed GPT-2 a selection of opening lines from some of history’s greatest literary works (including Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice”). My conclusion at the time was that the algorithm was capable of sticking with the subject matter for a few lines, but quickly became discombobulated and nonsensical. In other words, although A.I. is already capable of writing short news stories according to a fixed template (such as breakdowns of quarterly financial results), it didn’t seem like writers of longform and fiction pieces really had anything to fear.

This week, I decided to see how the technology had evolved since my last run-through. Although GPT-3 is out in the ecosystem, and testable, I wanted to try something with the well-established GPT-2: A custom generator.

A standard generator might have scraped text from millions upon millions of web pages in order to power itself, but the results are often mixed: For example, you could feed a GPT-powered platform a couple sentences of Jane Austin, only to have it spit back a mix of 2020 election news, gossip about 18th century British landed gentry, and a mangled Wikipedia entry.

A custom generator, on the other hand, allows you to provide the examples that the system uses to train itself and generate text. InferKit, created by Adam Daniel King, is an evolution of the ultra-popular Talk to Transformer, a public-facing GPT-powered tool that earned a lot of press from Wired and other venues. It also allows you to upload .txt or CSV files, which it then uses as the basis for its custom generator (uploads are capped at 20 MB or 20,000 documents).

For the purposes of this experiment, I fed InferKit a .txt file containing ~500,000 words of my fiction published over the past ten years, including novels, short stories, and poetry. It took about an hour to digest that data and learn from it. I then fed it a lengthy selection from the crime-fiction novella I’m writing right now:

Miller returned to his tiny apartment on Avenue B. A monk would have found the space nicely minimalist. The mattress on the bedroom floor was the largest piece of furniture. His money, along with an assortment of guns, rested beneath the floorboards of the short hallway that separated the bedroom from the bathroom.

On his way home, Miller had stopped at an all-night burger place on Avenue A and ordered the Big Jumbo Delight, two patties slathered with cheese and horseradish mayonnaise. He sat on the mattress, relishing each greasy swallow.

The Ricky deal was a mess, because everything Ricky did was a mess. But how had he managed to score that enormous house? Conmen dreamed of that big score, and virtually all of them failed to land it. Yet Ricky, dumb Ricky, had somehow tricked his way into a mansion.

Chewing the last bite of burger, Miller told himself that he would return to the townhouse in the morning, learn whatever there was to learn. Ten thousand dollars was nothing to wave off. And if Ricky was promising him that amount, it meant there was a lot more money in the pot.

Stripping off his clothes, Miller lay back on the bed, his hands folded behind his head. Pale light from the streetlamps trickled past the barred windows, throwing a maze of shadows over his body. By focusing on his breathing and the faint pulse of his heart, he could drive away his worries about fingerprints and the clown and his patterns and Ricky, drive it all far enough away that he could drift off…

Creak.

Oh, you bastard.

Creak. Creak. Creak.

That old man knew he was home.

Creak-creak-creak-creak.

(It’s a first draft; go easy on me.)

Here’s what an A.I. trained on ten years of my writing spat back as the next few paragraphs (I’ve inserted some paragraph breaks in order to give it a human-like flow):

The clock on the far wall chimed eight minutes too late, the door burst open, and the old man stumbled into the living room. There was a chair on the sofa, the curtains drawn. A pair of sunglasses rested on the coffee table, set on the floor.

Rick was nowhere in sight. Miller could hear a faint howl through the walls. The old man stumbled into the coffee table, leaning against it, startled at Miller’s actions. Miller sensed the fear in the man’s eyes, real, but the man had not seen him and yet. Miller waited for his wand, which never did arrive.

The old man, his shirt torn, his jeans ripped asunder, walked over to the couch. Rising to his knees, he bent down, brushing against the back of Miller’s neck with his fingertips. That’s a little rough, Miller mused.

It was a long way from Grandma’s farmhouse, and Grandma knew it, and you shouldn’t do that to people, the old man thought.

Taking the older man’s hand in his own, Miller took the sunglasses from the coffee table, stuffing them into his mouth. “Can I get a cup of coffee?” Miller asked. “You say I have a parole board?”

The old man looked at Miller with dark eyes. “What is that?”

Miller blinked. “You on parole, are you?”

Miller studied the old man’s features, reading his tense face. Dark circles under the dark eyes. And the old man’s mouth. Miller stopped when he noticed blood leaking from the corner of the man’s mouth. The old man reached into his shirt and yanked out the knife with a sad little whine, all purple and bony. Miller was certain the old man had seen him, though the man had none of that violence, no stalking in his victim’s mind.

The old man brought the knife up and bit into Miller’s cheek, hard. Miller, looking at the old man as he banged on the table, only saw a good man standing, blood running down his cheeks. Miller’s throat clenched painfully, hard.

“What is it?” the old man said, spitting the knife out.

Obviously, none of that is what I actually intended to write next. It’s not even close, unless I wanted to write some kind of horrific mashup of David Lynch and Robert Coover’s underrated surrealist classic Ghost Town. But here’s the startling thing: It’s a pretty good imitation of my prose style, even if the action is nonsensical. If you want to be charitable, you could describe the GPT-2/InferKit results as “dreamlike,” in the same way that dreams proceed without any adherence to plot mechanics or even basic physics. But if you’re willing to put concerns about logic aside, there’s a smoothness here that suggests A.I. is progressing.

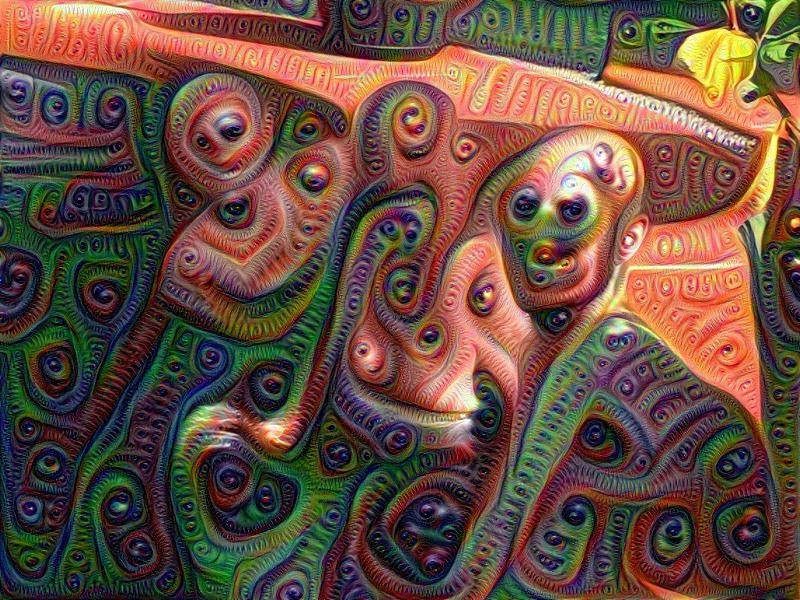

In many ways, this experiment echoes Google’s Deep Dream, which attempted to use a neural net to “learn” images. That resulted in some very trippy, dreamlike pictures. For example, this is three men in a pool:

Obviously, there are still substantial roadblocks before A.I. can comfortably take over fiction writing from human beings. A “general” A.I. (i.e., a “human-like” one; think HAL in 2001) would know that a human shouldn’t stuff sunglasses in their mouth. But these specialized, learning A.I.s that are filling our current world have no idea of existence beyond their highly specialized input; there’s no meta-awareness, no sense of structure.

And that sense of structure, of the broader world, is what is going to protect fiction writers for quite some time to come. Writers must make intuitive leaps; they (hopefully) have an instinctive sense of their work’s structure and its ultimate goal. Or as Nabokov put it, when discussing the writing of Lolita:

“These are the nerves of the novel. These are the secret points, the subliminal co-ordinates by means of which the book is plotted — although I realize very clearly that these and other scenes will be skimmed over or not noticed, or never even reached.”

These are nuances that necessarily elude the machines. You could upload all of Nabokov or Philip K. Dick to a platform running GPT-2 or GPT-3, and you might get a facsimile of their style and tone, but you wouldn’t get the structure or creativity. Humans writing press releases might have good reason to be frightened for their jobs over the next five years, but novelists may not have cause for concern for decades, if ever.

One marvels, though, at what Dick, high and feverish and smacking away at his typewriter keys, might have one with the concept of text predictors. Do androids dream of becoming great novelists?