The bank robber John Dillinger died on July 22, 1934. Or maybe he didn’t.

At the height of the Great Depression, Dillinger and his crew robbed at least a dozen banks across the Midwest, netting a small fortune (roughly $300,000, or around $5.7 million in 2019 dollars) in the process. He was an adherent of the “system” developed by the German bank robber Herman “Baron” Lamm, who plotted his heists down to the smallest detail — including block-by-block maps of potential escape routes. Dillinger was likewise meticulous; he also had a little flair; and soon enough he became a genuine celebrity to those who felt he was sticking it to the cruel, rapacious banks.

The 2009 film Public Enemies, directed by Michael Mann with his usual attention to historical fidelity, offers a suggestion of what a Dillinger robbery might have been like:

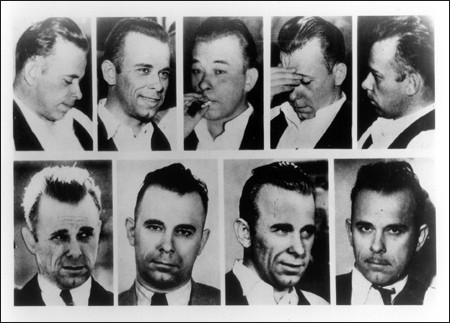

At the very least, it’s movies like that — along with decades’ worth of books, poems, television episodes, and other media — that reinforce the idea of Dillinger as a “gentleman criminal.” Like the other robbers of this so-called “Public Enemy” era, the amount that Dillinger actually stole was probably outstripped by the amount spent by the police and federal government to hunt him down. Dillinger managed to escape the dragnet a few times, and even had plastic surgery in an attempt to mask his all-too-famous identity; but eventually, the law caught up to him.

On that hot night in July, Dillinger was leaving Chicago’s Biograph theater with two female companions, one of whom had betrayed him to the FBI (they had seen “Manhattan Melodrama,” starring Clark Gable). Dillinger sensed the special agents staking out the theater’s perimeter, and ran for a nearby alley, but it was too late: the agents shot him four times, killing him instantly at the age of 31.

This is where things start to get a bit weird. But what American legend doesn’t come with its fair share of weirdness?

For years, rumors have persisted that the FBI gunned down the wrong man; that it was a lookalike, and not Dillinger, who died on the Chicago pavement. In “The Dillinger Dossier,” author Jay Robert Nash suggested the dead man was really one Jimmy Lawrence, a petty criminal who looked kinda-sorta like Dillinger.

Dillinger’s nephew, Michael C. Thompson, evidently believed those theories, because he tried to have his uncle’s body exhumed from an Indianapolis cemetery. “This evidence includes the non-match of his eye color, the (scar) shape and protrusion from the head, the fingerprints not matching, the existence of a heart condition, and the apparent non-match of the anterior teeth,” Thompson wrote in the affidavit for exhumation. (Carol Thompson, Dillinger’s niece, also reportedly filed an affidavit.)

Dillinger’s casket is buried beneath reinforced-concrete slabs and a “cap” of scrap iron and concrete, according to Time, which could make any exhumation a little bit difficult. A crew from the History Channel wanted to film the event as part of a documentary, but pulled out of the project in September 2019, following the cemetery’s refusal to let anyone dig up an infamous gangster on national television. Michael C. Thompson eventually gave up on exhuming his uncle, as well.

All that drama aside, chances are good that, yes, it’s really Dillinger under there. For starters, Dillinger did his best to burn his fingerprints off with acid, which generated those long-ago theories about the fingerprints “not matching.” Second, Dillinger’s sister Audrey reportedly identified an old, distinctive scar on the back of the corpse’s thigh, a souvenir from a childhood run-in with a barbed-wire fence — something difficult for a doppelganger to have.

Third, despite a bank-robbing career marked by a good deal of cardiovascular exercise — there’s nothing like knocking off a bank and shooting it out with the cops to hit that optimal heart-rate — Dillinger supposedly did have a heart condition, according to Patrick Weeks, physician at the Indiana State Prison where he did time:

“John Dillinger suffered from heart disease. He had a distinct heart lesion. The disease was organic. I told Dillinger that he should never subject himself to great mental or physical strain, because it might hasten his death. I was confident that he would follow my advice.”

Of course, the one test unavailable in 1934 — DNA testing — will solve this mystery once and for all. Chances are excellent that the gentleman bandit was buried in his actual plot. But isn’t it fun to wonder whether he actually got away with it?

It was fun to wonder whether he actually got away with it.